HOME

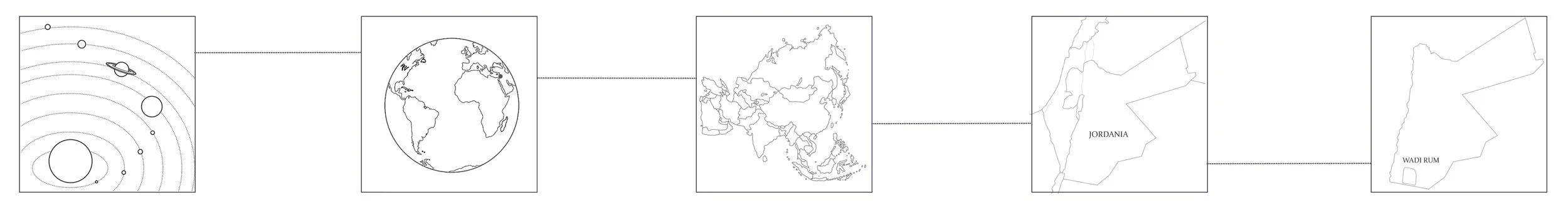

OF STARS: WADI RUM OBSERVATORY

MASTER THESIS 2019

2ND PLACE IN Z. ZAWISTOWSKI BEST POLISH DIPLOMA COMPETITION

The work merits distinction for its exceptional interdisciplinary approach, uniting knowledge from two fields—astronomy and architecture—and for its outcome: a functional technological structure shaped by a mature and refined architectural form. The boldness of reaching toward the stars is expressed with sensitivity, realized through discreet traces inscribed in the sand of the desert.

From the Jury’s opinion

Biś Lisowski, Juraj Hermann, Agnieszka Kalinowska-Sołtys, Marta Sękulska-Wrońska, Robert Konieczny, Przemo Łukasik, Przemysław Powalacz, Piotr Śmierzewski, Paweł Wierzbicki

Prologue

Astronomy and architecture are disciplines bound together by an enduring and inseparable relationship. Ancient civilizations left behind architectural artifacts designed for observing the night sky, revealing the earliest connections between these two fields—from the megaliths of Stonehenge to observatories in the Middle East dating back to the early Middle Ages. Monumentality has remained a defining characteristic of architecture serving astronomy, driven by the pursuit of maximum precision, achieved through the enlargement of measuring instruments—an expansion inevitably mirrored in architectural scale.

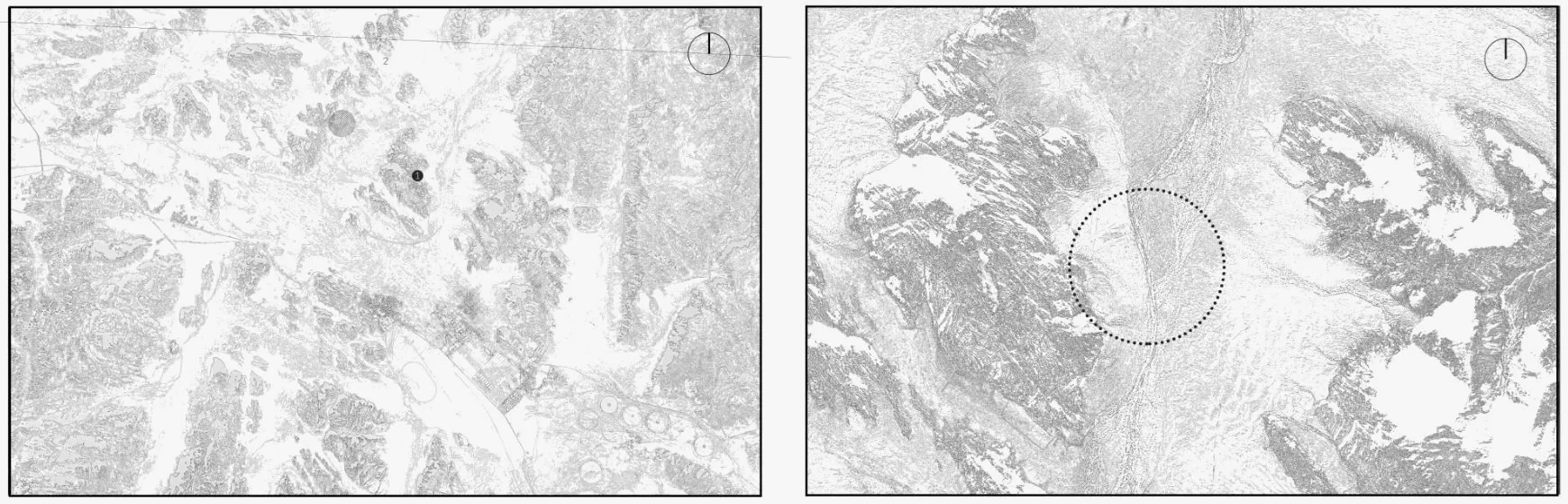

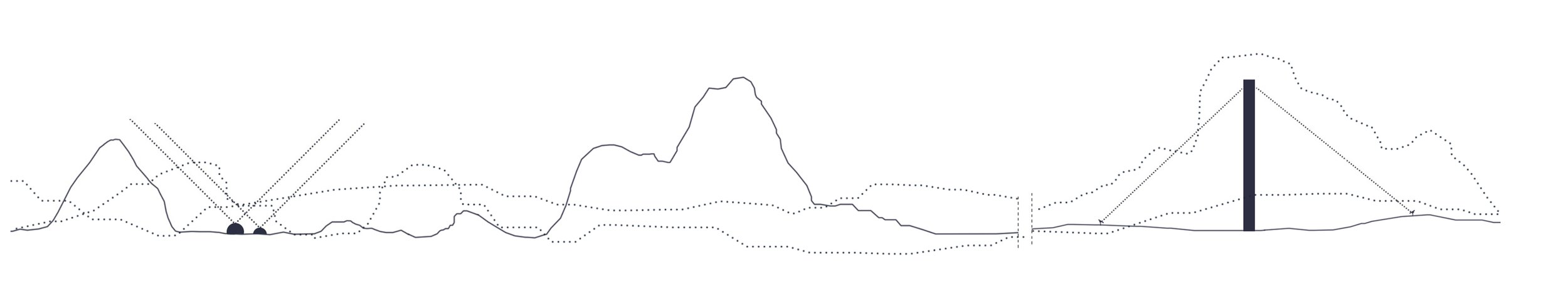

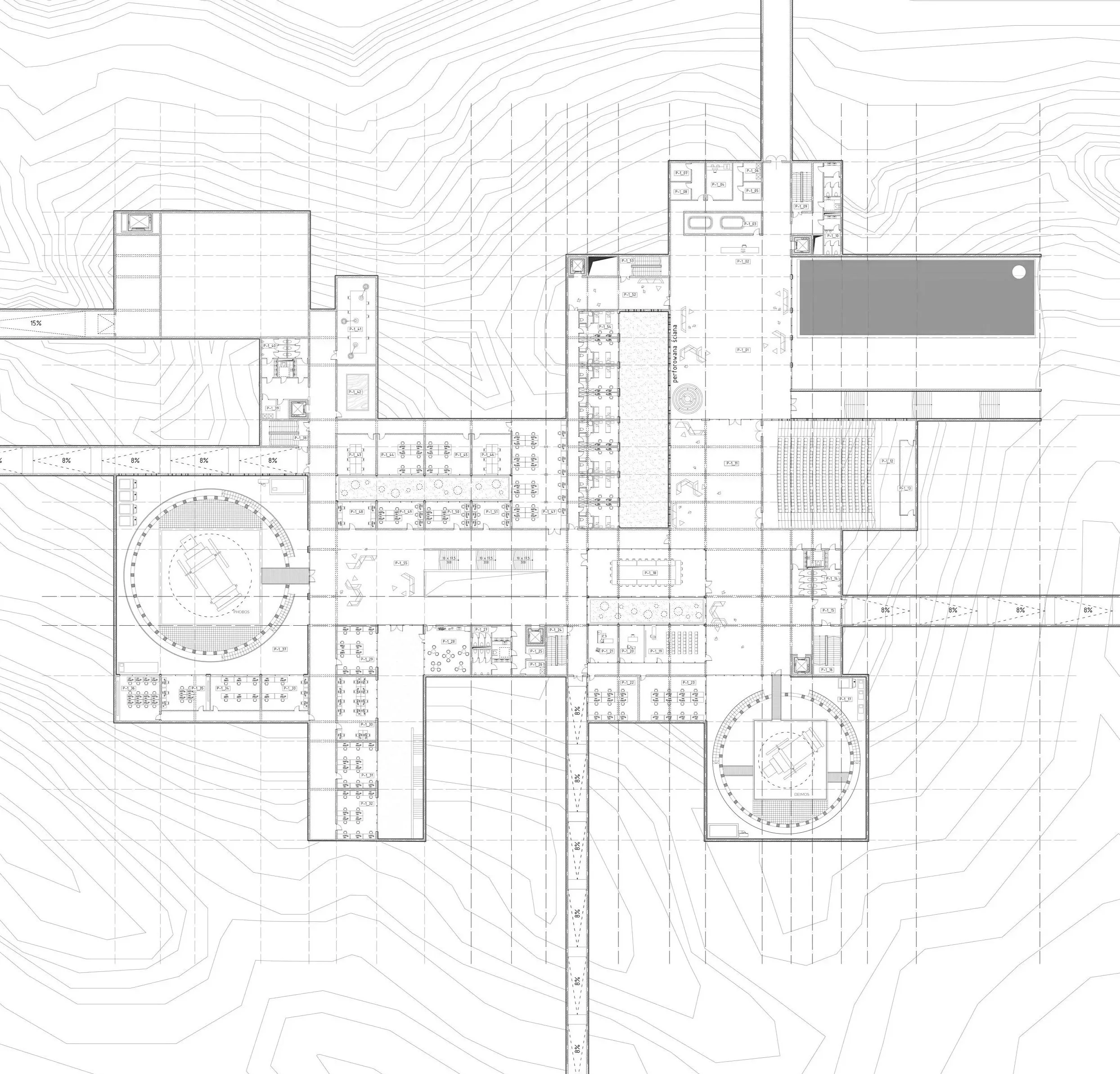

The challenge lies in designing a large-scale, functionally accessible, and visually powerful structure within a context where the undeniable beauty of the landscape stands in tension with monumental form. One possible response to this dilemma is to conceal the building within the terrain itself—an approach that, to some extent, reverses conventional architectural thinking. The modernist dictum articulated by Louis Sullivan, “form follows function,” is here redefined as “subtraction follows function.”

Subtraction follows function

The sense of unity between the designed object and the surrounding landscape emerges from an aspiration toward belonging rather than contrast, inspired by the carved, almost inevitable presence of Petra’s architecture. This cohesion is achieved through the use of mass-colored concrete, tinted to echo the hues of the natural rock. Employed consistently across exterior surfaces—facades, floors, stairs, ramps—and elements of small-scale architecture, the material allows the building to settle into its environment, not as an insertion, but as a continuation of the terrain.

A deliberate exception is made for the domes of the observatory. For technical reasons, their envelopes resist assimilation. Clad in reflective metal and partially submerged in the ground, they appear as foreign bodies—two surreal spheres suspended in the desert sands. Their estrangement is intentional: a quiet marker of the boundary between the earthly and the celestial.

Light enters the building through narrow bands of glazing, set within aluminum profiles finished in oxidized red (RAL 3009), a deeper register of the facade’s chromatic range. Solid external doors, fabricated from corten steel, introduce a material of time—one that records exposure, weathering, and duration. Inside, polished steel columns reflect fragments of their surroundings, multiplying space through reflection, while walls and floors of in-situ architectural concrete maintain a subdued, continuous tonality.

At selected thresholds—where interior and exterior begin to dissolve into one another—walls are punctured not by voids, but by light itself. Circular glass modules, embedded within concrete planes, produce the illusion of perforation. The light that passes through them recalls distant constellations, translating the logic of the night sky into architectural experience. These moments occur at the boundary between a residential patio and the research center’s foyer, along the side wall of the auditorium, and within the observatory hall adjacent to an open ramp—each a calibrated encounter between movement, light, and orientation.

In the hotel rooms, shading screens of perforated corten steel filter daylight. Their pattern synthesizes ornamental motifs characteristic of the Middle East, allowing cultural memory to operate through shadow rather than surface. A related gesture appears within the interiors, though reinterpreted: here, the decorated wall divides interior from interior. Instead of perforation, glass blocks of unconventional form are embedded within architectural concrete, creating a tactile and luminous relief.

In reference to the petroglyphs discovered in the rocks of Wadi Rum, the inner surfaces are conceived as carriers of inscription. Texts, informational graphics, and diagrams of stellar constellations are pressed directly into the concrete—transforming walls into silent witnesses, where architecture becomes both record and instrument, holding traces of knowledge as the desert holds the memory of the sky.

The Fifth Element

Working with a physical scale model proved essential in confronting the question of the fifth elevation. As the building is largely concealed beneath the surface, its primary architectural expression is not a facade but a composition revealed from above. The model allowed for a direct, tactile engagement with this condition, making visible relationships that remain abstract in drawing alone. The articulation of roofs, courtyards, cuts, and voids became the true field of composition—an exercise informed by the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, in which clarity, proportion, and restraint govern perception. In this inverted logic of architecture, the fifth elevation emerges as the building’s most decisive plane: a quiet order inscribed into the landscape rather than imposed upon it.