HOME

OF SHADOWS

INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION ENTRY 2025

3RD PLACE

The Home of Light explores the relationship between sunlight and spatial experience through a composition of contrasting volumes. The upper level is bathed in direct light, while the lower level, known as the Home of Shadows, remains recessed and introspective. The design is organized to capture the sun's movement, employing devices such as angled windows, thick walls, and voids to modulate brightness and cast shifting shadows. Light is treated as a narrative element—marking time, revealing surfaces, and guiding movement. The house stages a transition between illumination and obscurity, using architectural form to choreograph sensory and temporal perception.

via: Designing in the Dark: Buildner Announces 3rd Home of Shadows Winners ArchDaily, Published on May 27, 2025

Prologue

Architect has to be both a visionary and a strategist, anticipating future societal, environmental, and technological shifts to create spaces that remain meaningful over time. Global environmental problems are getting more and more urgent and concern over homes and their long-term sustainability must be carefully considered in architectural planning and urban development.

A single-family house is the least sustainable housing unit due to its high resource consumption, inefficient land use, and increased environmental impact. It requires more land per household, leading to urban sprawl, habitat destruction, and higher infrastructure costs for roads, utilities, and services. They also tend to have a larger per capita energy footprint, as heating, cooling, and maintaining detached structures demand more resources than shared walls in apartment buildings, which naturally reduce heat loss and energy needs. Additionally, single-family homes promote car dependency, as they are often located in suburban or rural areas with limited public transportation, further increasing carbon emissions. In contrast, denser housing options foster more efficient resource use, shared amenities, and reduced environmental footprints, making them a more sustainable choice for the future.

Another true luxury is natural light—a resource often taken for granted but one that comes at a cost. It shapes our well-being, enhances spatial experience, and breathes life into architecture, yet its presence is dictated by orientation, climate, and the ever-rising value of unobstructed access. In an era of dense urbanization, where shadows grow longer and windows narrower, natural light becomes not just an element of design, but a privilege—one that must be carefully captured, directed, and—in many cases, earned or replaced.

The competition’s challenge: to design a home without artificial light—provoked a deeper reflection, not only embracing limitations but imposing them with purpose. Rather than merely crafting an aesthetic play of shadows and illumination, it sought to signal something deeper: sunlight is not just an element of architecture but our most vital source of life, a force we must cherish.

In an open landscape, where sunlight pours freely and without obstruction, deep respect and pure love for natural light would undoubtedly guide toward an architecture of transparency—something akin to Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House or Philip Johnson's own home. A glass house, pure and elemental, harvesting maximum sunlight.

The Promised Land

I was born and raised in Łódź, a city in central Poland whose urban fabric was shaped by the rapid industrialization that took place in 19th century. Observing the stark contrasts within its dense, historic downtown: grand tenement buildings with high ceilings and generously proportioned windows bathed in sunlight, and the outhouses tucked within inner gloomy courtyards remained in perpetual shadow, I have studied the role of sunlight. This striking hierarchy of space conveyed an undeniable message—light is a luxury and has its costs. It defines architecture, influences the way people live, and shapes their perception of their place in the world.

In the modern era, one might assume that sunlight has lost its significance. Electricity has granted us independence from natural light, reducing our reliance on the sun's rhythms. Yet, in truth, light has only gained a deeper, more profound meaning.

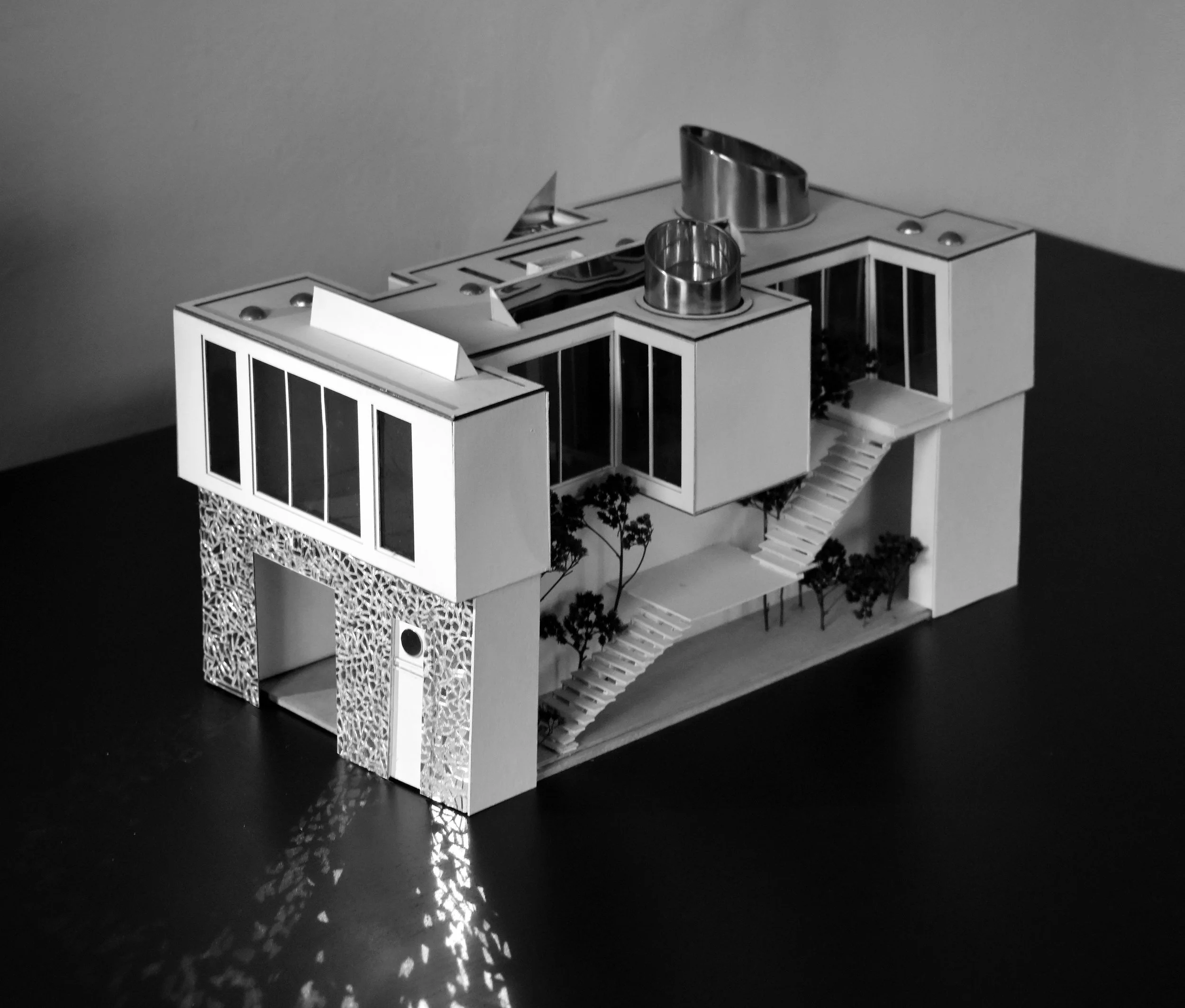

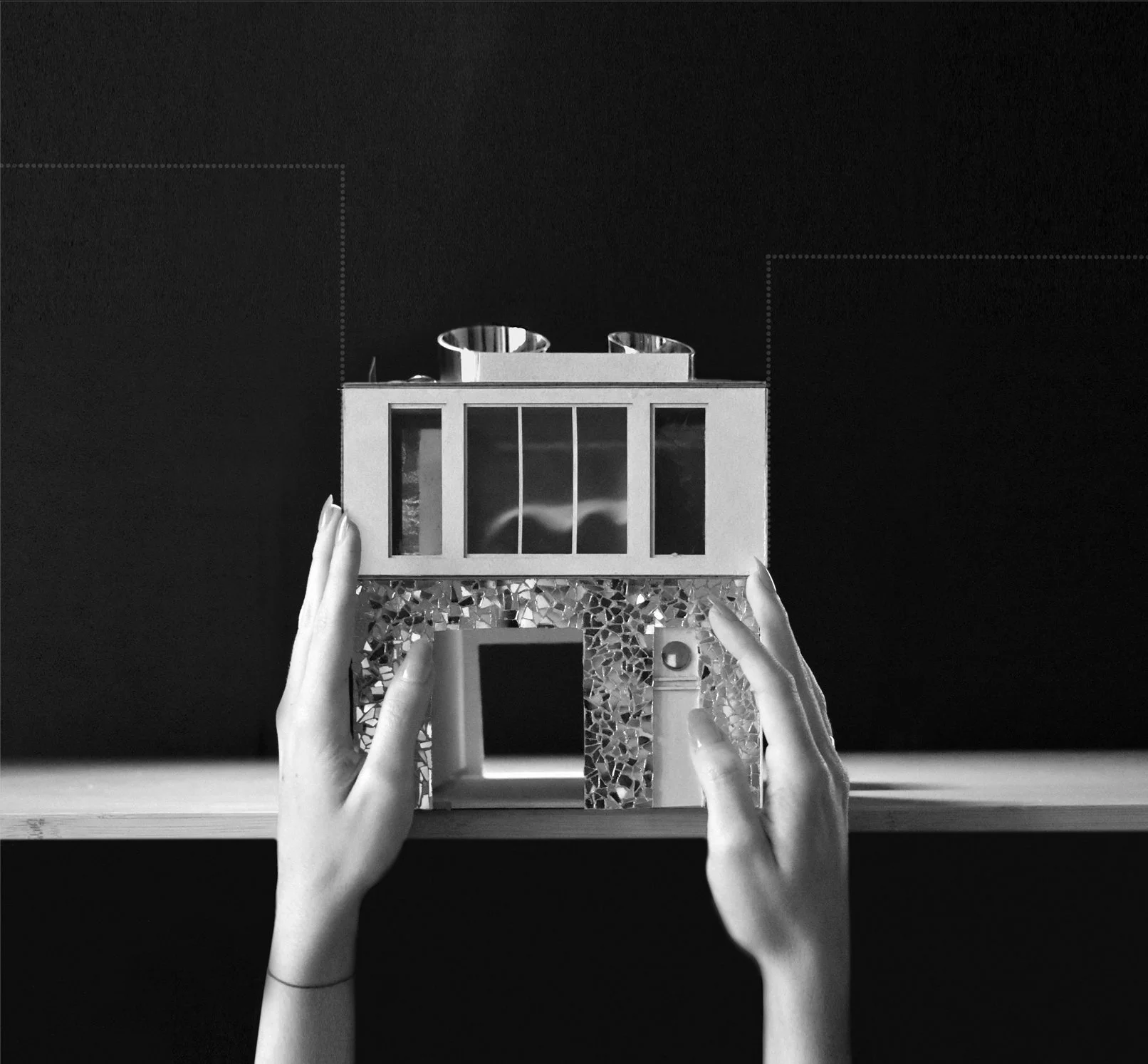

Given the competition’s requirements, a physical scale model was chosen over digital visualization. Despite remarkable advancements in rendering technology, digital tools still struggle to capture the subtleties of natural light—particularly caustic effects and realistic reflections. A physical model, by contrast, offers an undeniable advantage: it allows for precise observation of how light moves, bends, and interacts with surfaces.Through direct observation, design choices are guided not by approximation, but by tangible, real experience.

Light seems to hold a certain magic that is hard to translate to the machine language.

For centuries, light has been a metaphor for truth. In an age of technological revolution—propelled by quantum computing and artificial intelligence—the human need for shelter takes on a new dimension. Beyond mere efficiency, architecture must offer shelter from the hypnotic, mass-produced flow of digital information. It must create places that ground, restore, and invite reflection, anchoring human presence in an era of accelerating abstraction. The Home has always been—and must remain, a sacred space.

Digital design has introduced a profound detachment between architect and building, placing them in parallel worlds—the real and the virtual—separated by the glass of a screen, with no room for direct physical interaction during the creative process.

Władysław Reymont’s novel The Promised Land vividly captures Łódź at the threshold of a new industrial age. More than a century later, its themes remain strikingly relevant. As machines no longer replace just physical labor but encroach upon human thought itself, the novel’s vision provokes essential questions: What is truly gained in the relentless march of progress? And what is irretrievably lost?

Człowiek stworzył maszynę, a maszyna człowieka zrobiła swoim niewolnikiem; maszyna będzie się rozrastać i potężnieć do nieskończoności i również wzrastać i potężnieć będzie niewola ludzka. Voila! Zwycięstwo kosztuje zawsze więcej niż przegrana!

Władysław Reymont, Ziemia Obiecana, 1899

The man made the machine and the machine made the man its slave; the machine will grow and become more powerful to infinity and also the human slavery will grow and become more powerful. Voila! Winning always costs more than losing!

Władysław Reymont, The Promised Land, 1899

Plot Twist

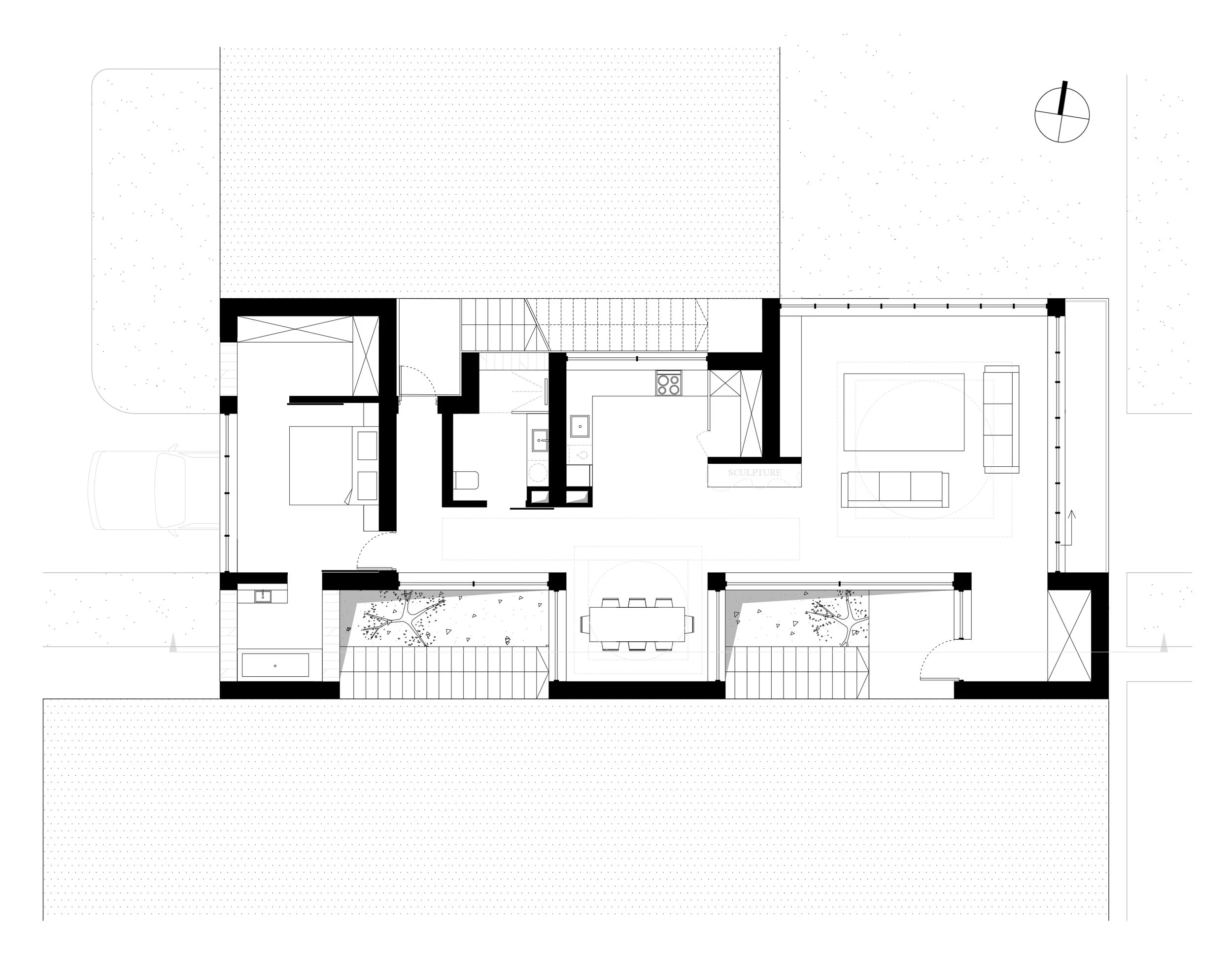

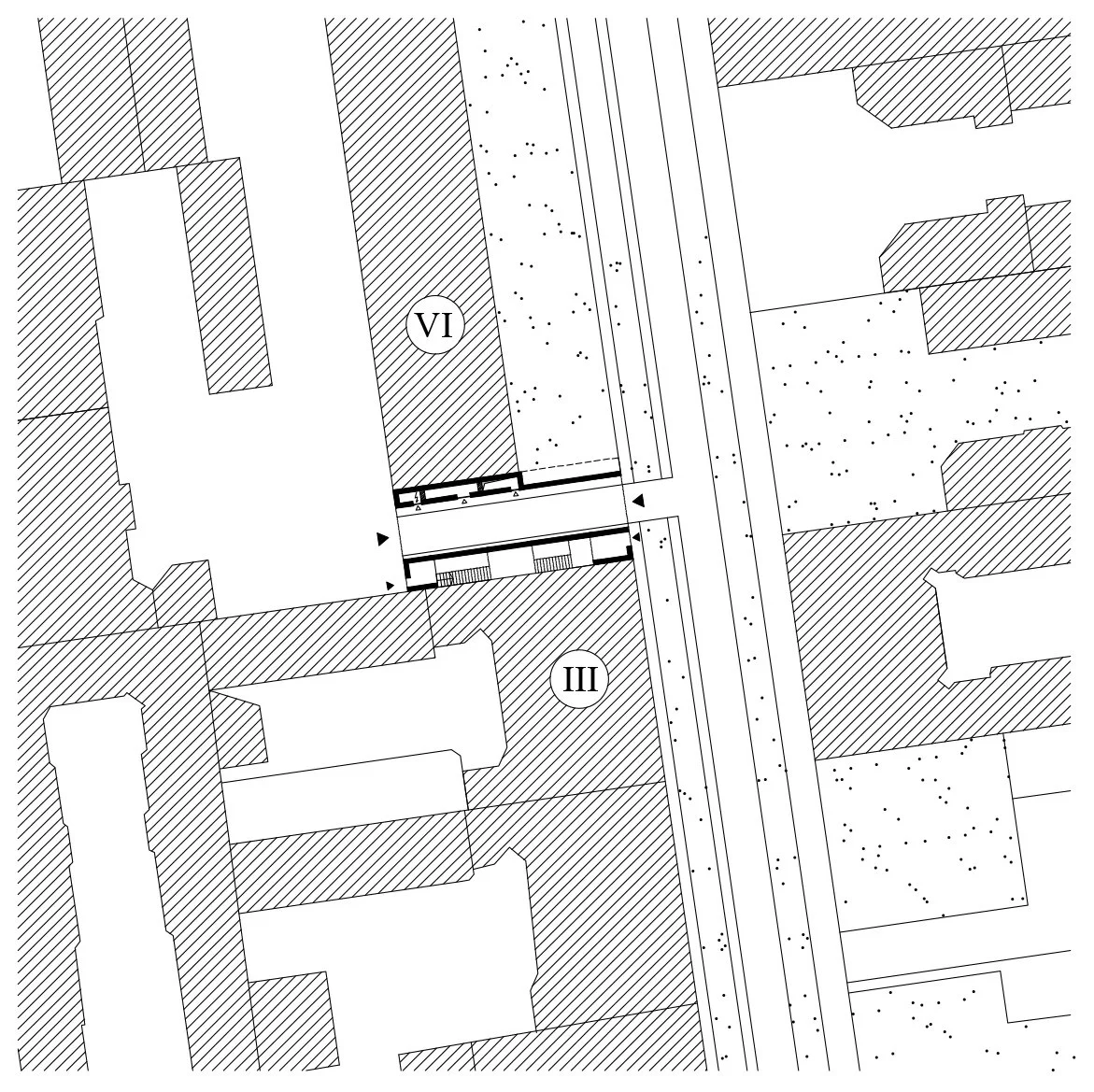

The plot located by the Wschodnia 13 St. in Łódź is a narrow strip of land, with sunlight limited by it's surroundings.

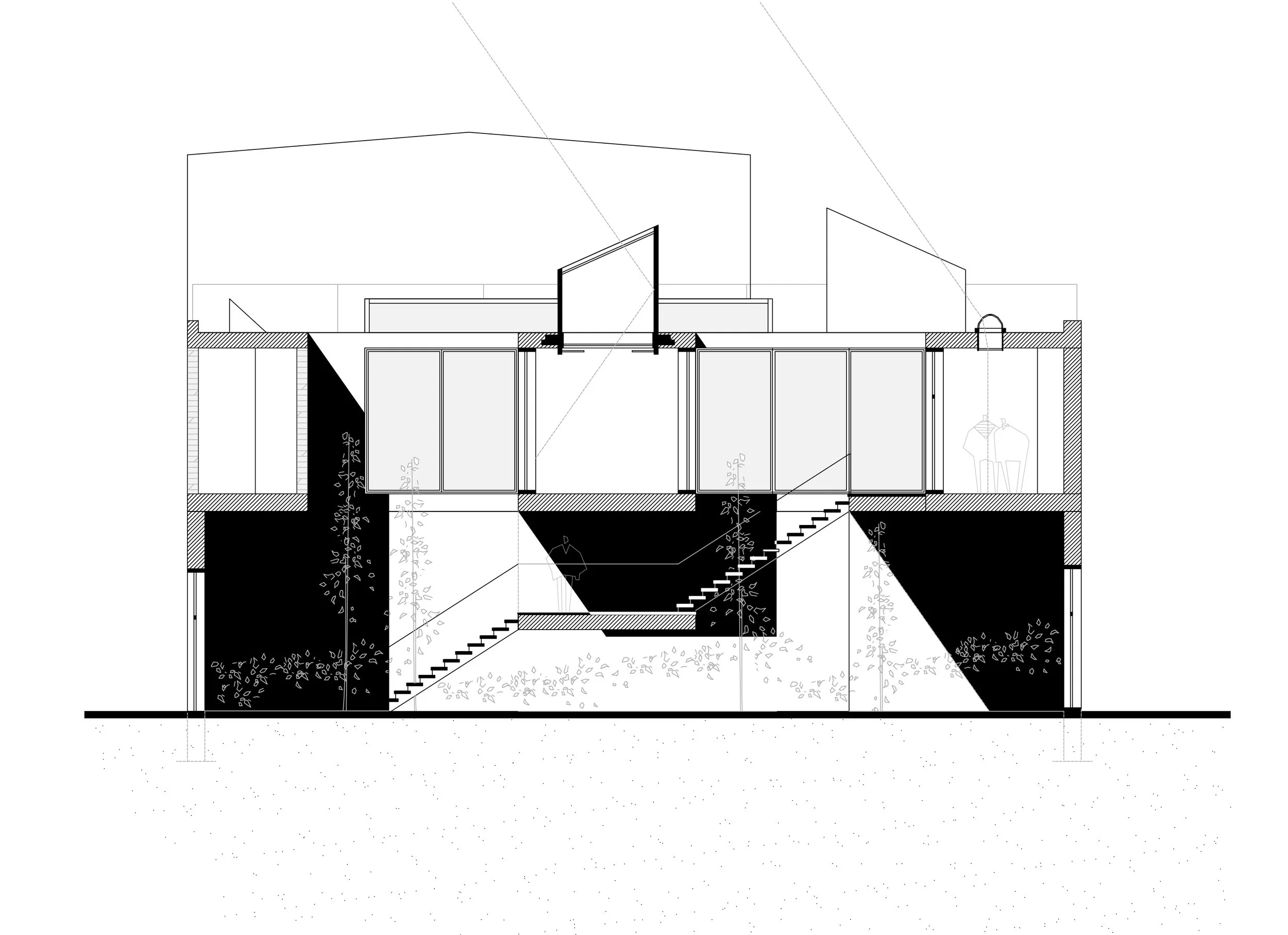

To ensure that the neighboring structures continue to function properly the house had to be elevated on pillars, to create a passage for pedestrians and vehicles and allow for a dynamic interaction between the architecture and the existing urban environment.

The street names in this quarter are named according to the directions of the world, which is a delightful coincidence. Wschodnia in Polish means Eastern.

The design carefully balances the need for daylight harvesting with the necessity of privacy. To achieve this, in a living room area a mirror glazing is employed. Adjustable shutters further contribute to this dynamic system, doubling as sun catchers with highly reflective surfaces on one side to redirect light into the interior. In more intimate spaces such as the bathroom and dressing room, glass bricks provide a diffused glow, maintaining privacy without compromising natural illumination.

In an open setting, a glass rooftop would have been the ideal solution, but the constraints imposed by the surrounding buildings required a more strategic approach, integrating several gimmicks to optimize daylight within the space.

Here comes The Sun

1. Pasaż Róży [Passage of Rose] is an artwork by Polish artist Joanna Rajkowska, inspired by the experience of her daughter Róża's illness, who was diagnosed with eye cancer shortly after birth. The walls of the tenements in the passage between Piotrkowska and Zachodnia Streets in Łódź were lined with a mosaic that gives an image broken into thousands of mirrors. The author, assisted by city residents, lined the buildings with light—sensitive mosaic, mirror—like architectural skin. The place has become a symbol of Łódź, legible to anyone who has visited it at least once.

2. Linear top light duckts system draws inspiration from the skylight prototype made by the members of Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, University of California published in 1994 [Beltran, L. O., et al. The Design and Daylighting Evaluation of Advanced Light Shelves and Ligt Pipes]. It uses a combination of reflective, spectrally selective and diffusig films; in the modyfied design fresnel lens and luxfer prisms are added to catch the sunlight directly and illuminate the celling throgh the day. The system itself is steady; the movement is directed by the Sun itself, adding a soft, ambient light. Traditional windows were replaced by glass blocks in the bathrooms and a dressing room—distorting the view to ensure privacy while allowing light to filter through. Inside, they create delicate, ever-changing patterns of light throughout the day, offering a meditative experience.

3. The living and dining rooms feature lunettes designed to capture sunlight through their precisely truncated forms. Their positioning is manually controlled, allowing the user to modulate the intensity of light within the space. Additionally, a mechanism inspired by a camera aperture provides further refinement, enabling precise adjustment of the light entering the interior.

Just as cinematographers sculpt light to shape mood and meaning, the inhabitants of this space become active participants in a cinematic experience, adjusting the interplay of shadows and brightness as one would frame a shot. The gleaming circle glides across the floor and walls like a wandering spotlight, transforming fleeting moments into something significant. The light is both a medium and a message—shifting, ephemeral, and deeply intentional.

4. The solar dome skylights are engineered to continuously capture and refract sunlight to harnesses sunlight into interior spaces, ensuring optimal light intake regardless of the sun’s position, illuminating spaces with a consistent, diffused glow.

An additional system of heliostatic mirrors is installed to track the sun’s movement, directing its light onto the light sculpture throughout the day. Acting as precision reflectors, mirrors enhance the sculpture’s presence by intensifying and shaping the light, creating a theatrical interplay of illumination and shadow, transforming the sculpture into a dynamic focal point that responds to the shifting angles of reflected sunlight. However, heliostats can be turned off, letting the sculpture follow the natural rhythm of the sun, embracing the organic transitions of light and shadow. This adaptability offers a choice between engineered spectacle and unfiltered solar movement.

5. The magic of everyday life: a steel jug designed by Danish designer Henning Koppel. Its geometry makes the object flare with subtle, ethereal lines painted by the sunlight on the white wall. This moment was a turning point, and became the inspiration for the sculpture—a monument of light, crafted from polished metal and precisely designed to interact with the sun. Geometry of its reflective surfaces captures and redirects natural light, creating dynamic reflections that shift throughout the day. This is a rendezvous between art and a simple law of physics: the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection. As the sun or it's reflection moves, the sculpture frames and projects abstract, ever-changing virtual images, transforming the perception of space. It is both an object and an experience—an interplay of light and time. The sculpture titled Geometry of Feeling is currently in the making, becoming a separate artwork inspired the theme of the competition.

The purpose of the architecture is not to beautify or humanize the world of everyday reality, but to open a new view into the second dimension of our consciousness, the reality of dreams, images and memories.

Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, 1996